History

From the origins to the donation of 954 A.D.

The first historical evidence of Seborga can be traced back to the fifth century BC, when the pirate raids pushed the inhabitants of the coastal strip of the extreme western Liguria to take refuge in the hinterland, where it is however conceivable that some sporadic settlements were already present around the 2000 B.C.

Around 250 BC, Western Liguria, at the time part of Celtic Gaul, was conquered by the Romans. The settlements were registered and classified as “burga” and the inhabitants began to take on an orderly structure, with the establishment of rules of common life. The Romans were initially not well regarded by the local population, since the latter was considered barbaric and could not enjoy the benefits of the ius italicus, that is, a set of privileges concerning especially the economy and tax pressure; the inhabitants therefore always held a hostile attitude towards the Romans, which ceased only when they obtained the Roman citizenship.

Liguria subsequently suffered the invasion of some barbarian populations, the Ostrogoths and the Byzantines, until in 643 it was conquered by the Lombard king Rothari. In the early eighth century, given the intensification of the raids by the Saracens, some burga, including Seborga, were fortified for defensive purposes and became castra. In 770, following the marriage between Desiderata, daughter of the Lombard king Desiderius, and Charlemagne, the Lombard Kingdom (and therefore also Liguria) was annexed to the Kingdom of France, which in turn was incorporated into the Carolingian Empire. In 789 Charlemagne, as part of the organization of the empire, established the County of Ventimiglia (including Seborga), initially dependent on the March of Tuscany. In 890 the Marquis of Tuscany Adalbert appointed his son Boniface II as Count of Ventimiglia – the first to boast this title – who managed to make the County of Ventimiglia independent from the March of Tuscany.

Bonifacio, Count of Ventimiglia, elected the Castrum of Seborga as his and his descendants’ burial place, changing the name of the town to Castrum Sepulchri or Castrum de Sepulchro, although in Seborga the remains of noble tombs have never been found.

Seborga, feud of the monks of Saint Honoratus of Lérins

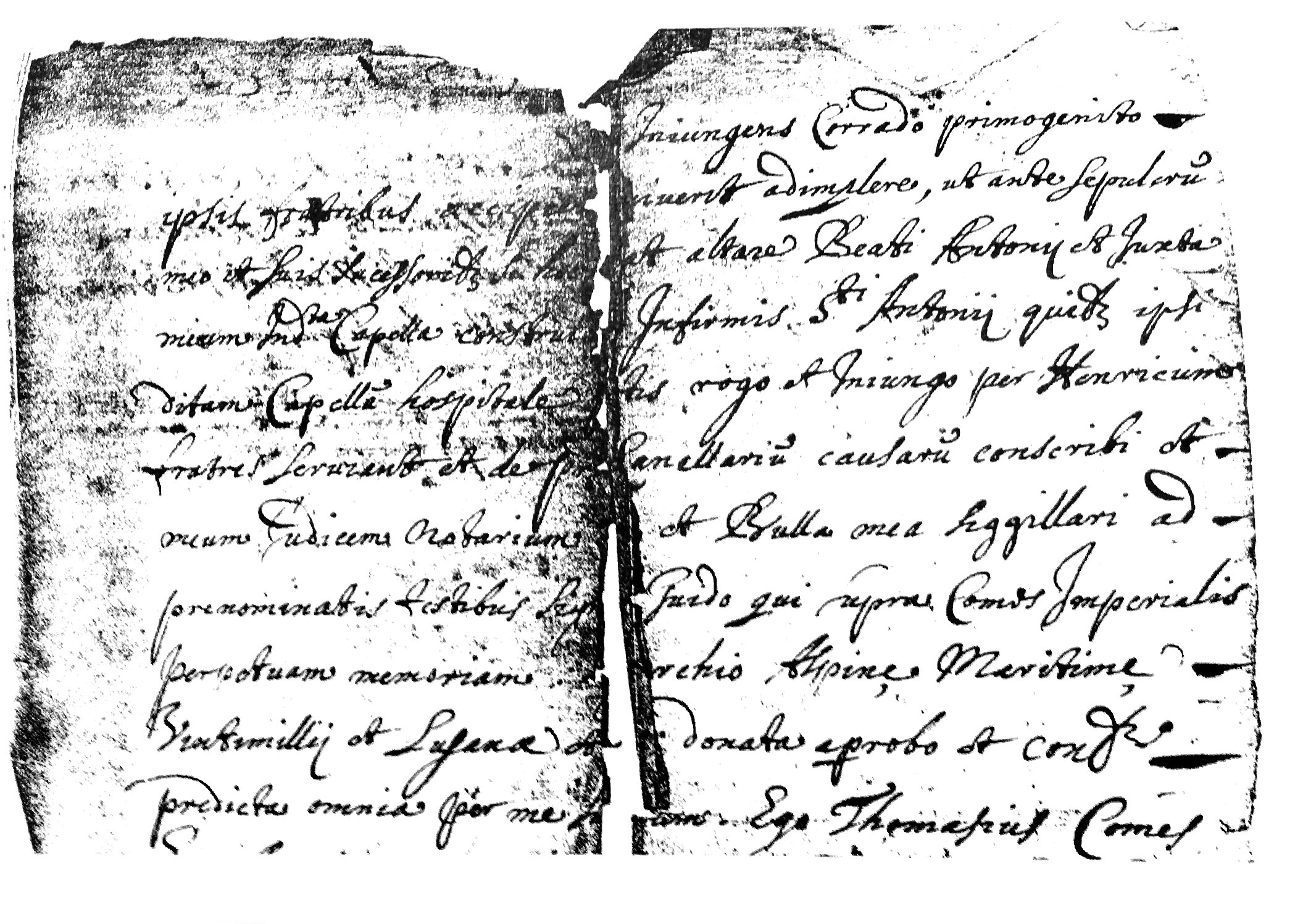

On 3 April 954, Count Guidone of Ventimiglia, who was about to leave to fight “contra perfidos Saracenos” alongside William the Liberator, Count of Provence, donated the territory of Seborga to the Benedictine monks of the Lérins Abbey; this abbey was located – and still is – on the Lérins Islands, located in front of Cannes and at the time part of the County of Provence, division of the Kingdom of Arles (which was born in the meantime). The notarial deed of donation, today preserved in Turin, is considered by almost all historians to be an apocryphal document, however it is certain that the donation actually took place: in fact, an original document has reached the present day bearing a sentence of 1177 about a dispute that arose over the borders between the properties of the monks and those of the Counts of Ventimiglia, and in this authentic document the donation is explicitly confirmed. The donation concerned an area of approximately 14 km2.

Starting from 1079, with the authorization of Pope Gregory VII, according to the widespread custom of that time, the abbots of Lérins were able to claim the title of Princes-Abbots of Seborga, enjoying the so-called “mere et libero imperio cum gladii potestate” (i.e. the right to impose the death penalty, however never exercised in Seborga). Consequently, the Abbot claimed to be independent of the secular clergy and to depend exclusively and directly on the Pope (“nullius dioecesis“). This circumstance also caused tensions with the Bishop of Ventimiglia, who claimed to be the legitimate spiritual authority (thus being able to collect tithes on the crops), and will provoke numerous interventions by various Popes in favor of the theses of the Abbot of Lérins during the XII century.

Sovereignty belonged to the Abbot of Lérins, who nevertheless rarely exercised it. The same title of Prince of Seborga began to be used especially from the seventeenth century. In fact, the Podestà commanded in Seborga: he was often chosen by the Prince-Abbot and in any case always had to be approved by him. His main task was to judge those accused of having committed a crime on the territory of the Principality. Two Consuls reported to the Podestà and had purely formal functions (for example, the presidency of the Parliament of the Heads of Families or Priors, perhaps chosen among the guardians of Seborga) or in any case modest tasks (for example, collection of tithes, reports of crimes, closing of the city gates). Finally, the Mayors depended on the Consuls, who were in charge of bureaucratic-administrative functions and remained in office for only one year. The Lérins Abbey mainly dealt with foreign affairs, while internal affairs were managed by the Podestà, who in any case reported to the Prince.

Over the following centuries Seborga was repeatedly the object of attention from the Republic of Genoa (which in the meantime had incorporated the pre-existing County of Ventimiglia since 1030), which tried several times to annex it, irritated by the fact of having an enclave inside its territory that escaped its political control. Even in Seborga itself, conflicts arose between the monks and the local inhabitants, who often refused to pay tithes on the rather scarce harvests; the monks were forced several times to ask for loans to be able to maintain the village.

In 1261 the “Statutes and Regulations” of Seborga were written by Giacomo Costa at the behest of the Prince-Abbot Bernardo Aiglerio.

On 16 January 1515 Pope Leo X, at the request of the Prince-Abbot Augustine Grimaldi, placed the Lérins Abbey, which was under the regime of commendation from 1464, under the jurisdiction of the Benedictine Congregation of Montecassino, which in turn transferred its power of control to the Abbot of Montmajour in Arles.

Following some bad agricultural years, Seborga’s precarious financial situation worsened gradually. Also to try to resolve the situation, on 24 December 1666 Prince-Abbot Cesare Barcillon decided to contract out the management of a new mint to beat his own coins to Bernardino Bareste of Mougins: the luigini. Seborga then closed the mint in 1688, after the King of France formally protested because of a management contract granted to a Huguenot from Nimes, Jean D’Abric, who had been accused of minting counterfeit coins. The material used for minting the coins was then sold in 1719 by the Podestà of Seborga Giuseppe Antonio Biancheri to the Republic of Genoa, in partial repayment of a previous debt that the monks had contracted with the latter.

The right to mint coins was re-exercised in contemporary times by Prince Giorgio I in the years 1994-96 and later by Prince Marcello I, with the issue of circulating and commemorative luigini.

Further information about the coining of the luigini can be found on the page The Luigini.

Therefore, the economic-financial situation did not seem to improve and the monks began to meditate on selling the village.

The monks sell Seborga

The negotiations

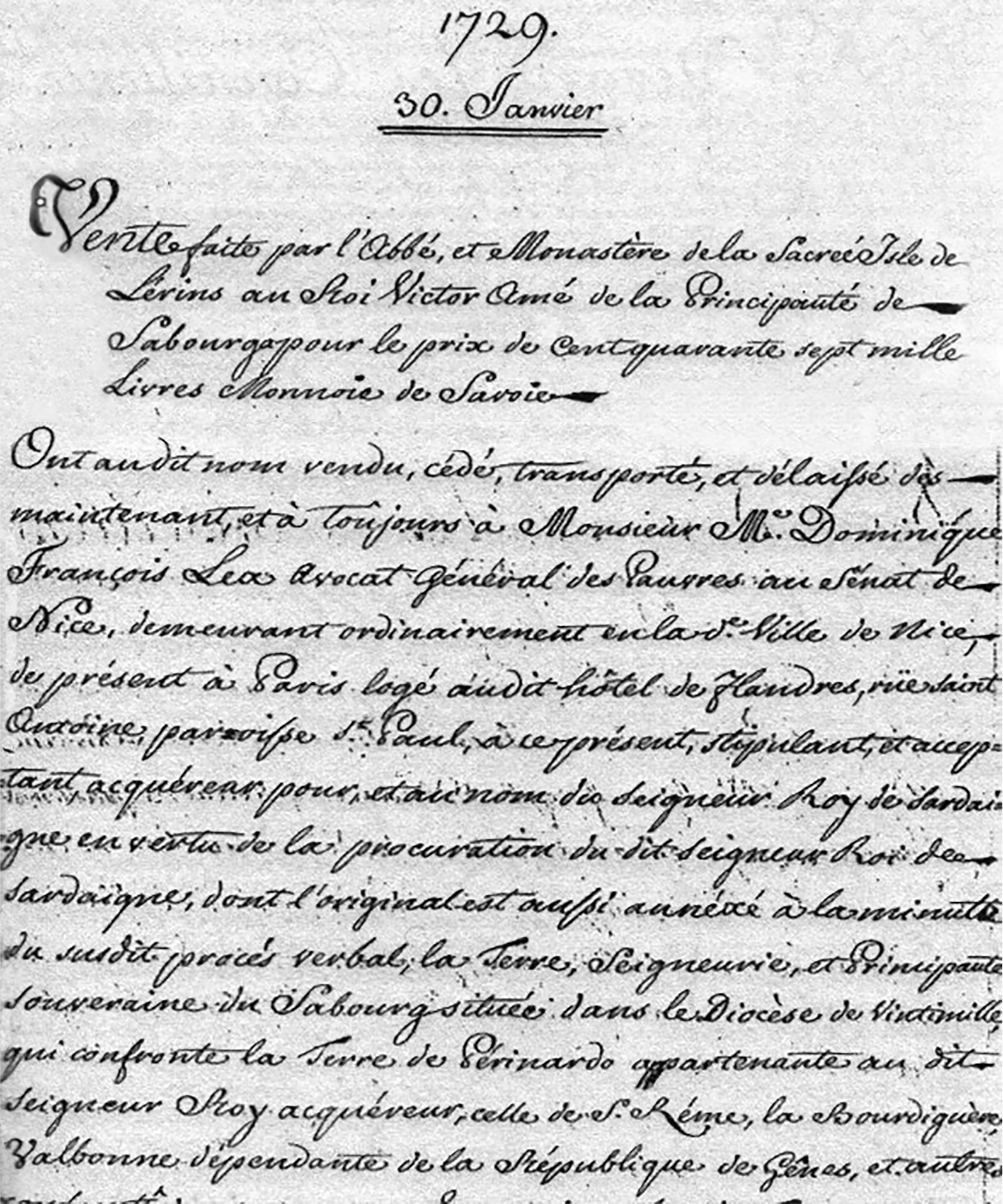

In 1697, while Giuseppe de Meyronnet was Prince-Abbot, a first preliminary sale was drawn up with the Duke of Savoy Victor Amadeus II. However, the Republic of Genoa, which continued to badly tolerate the hypothesis of having an enclave in its territory and which therefore wanted to take possession of Seborga at any cost, put pressure on King Louis XIV of France, on the Bishop of Ventimiglia and on Pope Innocent XII to obtain an extension of the negotiations with the Savoy. In the meantime, some private individuals also came forward, such as the Modenese Count Vespucci, Françoise-Athénaïs de Montespan (official lover of the King of France Louis XIV), the Bolognese Filippo Ercolani and the Grimaldis of Monaco, as well as some figureheads for the Republic of Genoa, such as Ernesto Lercari from Taggia, Renato Sauli from Genoa, and the Republic of Genoa itself, through the Marquis Doria. In reality, the monks were never interested in these offers, being determined to sell Seborga to the Savoy, from whom they wanted to obtain the highest possible price. In fact, negotiations resumed only in 1723, when the Duke of Savoy Victor Amadeus II appointed the lawyer Francesco Lea as his plenipotentiary representative for the negotiations. In 1728 the last clearances arrived from the Abbot of Montmajour (who since 1515 had control functions over the Lérins Abbey) and from the King of France Louis XIV.

The sale to Victor Amadeus II of Savoy: why Seborga is still independent today

On 30 January 1729 the deed of sale of Seborga was signed in Paris in the presence of the lawyer Francesco Lea, representing the King of Sardinia, and of Fathers Benoît de Benoît and Lambert Jordany, respectively treasurer and dean of the Lérins Abbey, in representation of the Prince-Abbot Fauste da Ballon.

This act, which was never registered, did not explicitly provide that the King of Sardinia would acquire sovereignty over Seborga (so much so that “Prince of Seborga” never appears among his official titles), but simply that Seborga’s territory would become his personal possession, over which he would exercise the role of protector (ius patronatus); not surprisingly, the purchase (which was never paid) should have been made with the personal finances of the king and not with those of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

On these theses, the Principality of Seborga still claims today that Seborga is independent: with regard to the sale of the Principality in 1729, the sovereignty over Seborga would have fallen ipso iure on the people of Seborga in the absence of an explicit clause providing for the transfer of it to the King of Sardinia, and Seborgans didn’t actively exercised it for almost two centuries, merely agreeing tacitly to the fact that the effective management of the country was entrusted to the King of Sardinia through his emissaries. The annexation to the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 and to the Italian Republic in 1946 would therefore be unilateral and illegitimate acts, because they violate the legitimate sovereignty of the Seborgan people. The exile of the Savoy, in 1946, also led to the end of the ius patronatus.

In 1751 the Holy See confirmed the nullius dioecesis status of Seborga.

Seborga today

The people of Seborga meet freely and spontaneously on 14 May 1963 and elect Giorgio Carbone as Prince of Seborga, a citizen of Seborga passionate about history who has always been a supporter of independence from the Italian state, which today de facto illegitimately exercises its sovereignty over Seborga. Especially since the nineties, Prince Giorgio I refounded the institutions of Seborga: Seborga took up the ancient sovereign coat of arms, the white and blue flag, the ancient motto “Sub Umbra Sedi“. On 3 April 1994, elections were held for the appointment of a constituent government. On 23 April 1995 the people approved the new constitution (the “General Statutes” and the “Regulations”) with 304 votes in favor and 4 against. A few months later, on 24 September 1995, new votes were held to elect the members of the Crown Council, the executive body of the Principality. Notwithstanding the General Statutes, Prince Giorgio was re-elected for life, taking the oath on 13 October. Also in 1995, the minting of the luigini resumed, which however was suspended the following year, and stamps were printed for the first time; a Corps of Guards was established, a national anthem, a new flag and a car license plate were adopted. The reactivation of Seborga’s sovereignty revived tourism and boosted the curiosity of media, gradually more and more interested in the reality of Seborga and its history.

On 20 August 1996, the anniversary of Saint Bernard, Giorgio I officially reaffirmed the independence of the Principality, with the following proclamation: “We Giorgio I, Prince of Seborga by the grace of God and by the will of the Sovereign People, by law and in international law in force in all states with democratic and modern constitutions, reaffirm and decree the territorial, juridical, religious, civil, moral and material sovereignty of the Principality of Seborga“. On 5 April 2007, Judge Erika Cannoletta of the Sanremo Court, issuing a sentence on a dispute between Seborgans, declared that the Italian State had no jurisdiction over Seborga: “[…] There can be no exclusive jurisdiction over a State not recognized as sovereign by the Italian State but considered as such by other communities and/or foreign States recognized by Italy“. The judge sent the documents to the Italian Constitutional Court and notified her ordinance to the Prime Minister and to those of the two Chambers. On the other hand, on 14 January 2008, the Constitutional Court declared the inadmissibility of the question of constitutional legitimacy. A new appeal was therefore initiated at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, which was however judged inadmissible on 12 December 2012.

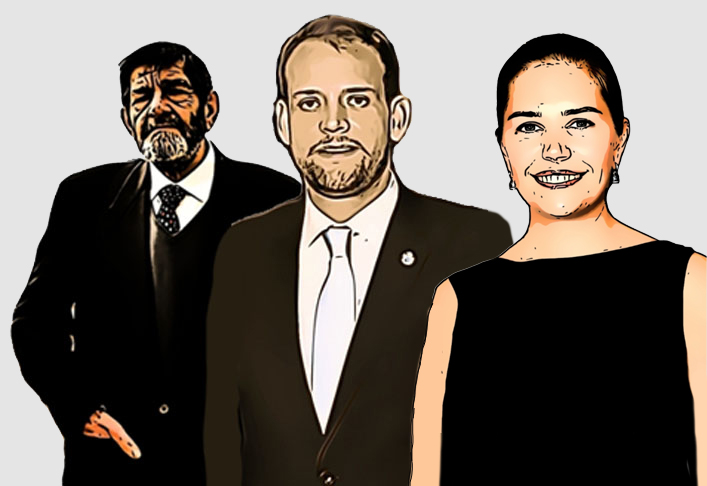

Prince Giorgio I (who in the meantime fell ill with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) passed away on 25 November 2009. On 25 April 2010 Marcello Menegatto was elected Prince of Seborga (with the name of Marcello I) through open elections and was re-elected for another seven years on 23 April 2017.

On 12 April 2019, Prince Marcello announced his intention to abdicate, remaining in office until the election of his successor. On 10 November 2019 Nina Menegatto was elected Princess of Seborga, the first woman in history to hold this office.